How I Lost My Mother

Well. That’s a disingenuous title. This essay won’t answer that prompt. Does that make it click bait?

The truth is I don’t really know what happened. I don’t think either of us does. We used to be very close. We finished each other’s sentences. She was my first phone call for news, good or bad. Looking back I can see that she manufactured some of that closeness by keeping me isolated from my peers, partly (mostly?) so that she didn’t need to confront her own social anxiety. If I had a problem with a peer, the answer was always that the girl must be jealous of me. I never had to look at my own behavior or examine the qualities I was lacking that are required to be a good friend. She grew in me a mistrust of women that it has taken me decades to chop down, branch by branch, and I still find myself clawing at the roots. That, coupled with my own social awkwardness, left me lonely, dependent on my relationship with her or, as I grew, on romantic relationships as the only ones that I could trust, fostering a deep misunderstanding that romantic love was somehow the only kind of love that mattered, the only kind of love that made me valuable. The fact that I married a kind, honest, and wonderful partner at 24, and we have a healthy and thriving marriage of over a decade today is somewhat of a miracle and a mystery considering my upbringing and history.

The last time we spoke, I told her that the kids are growing up, and that I couldn’t pause that for her to get her head right. I told her that my friend’s mom, who lives in Chicago, has held Jack more times than she has even though she only lives twenty miles away, that Henry doesn’t even know who she is, that O and P only remember that she has a pool at her house. I told her that I was tired of chasing her, tired of waiting for her to call, to engage. I told her that I was fine, that my life is filled with people who lift me up and meet me where I am and love me in spite of and because of who I am, right now, today, people who see me. I told her that my kids are fine too, because that same community that holds me, holds them too. I told her I just didn’t want her to miss out.

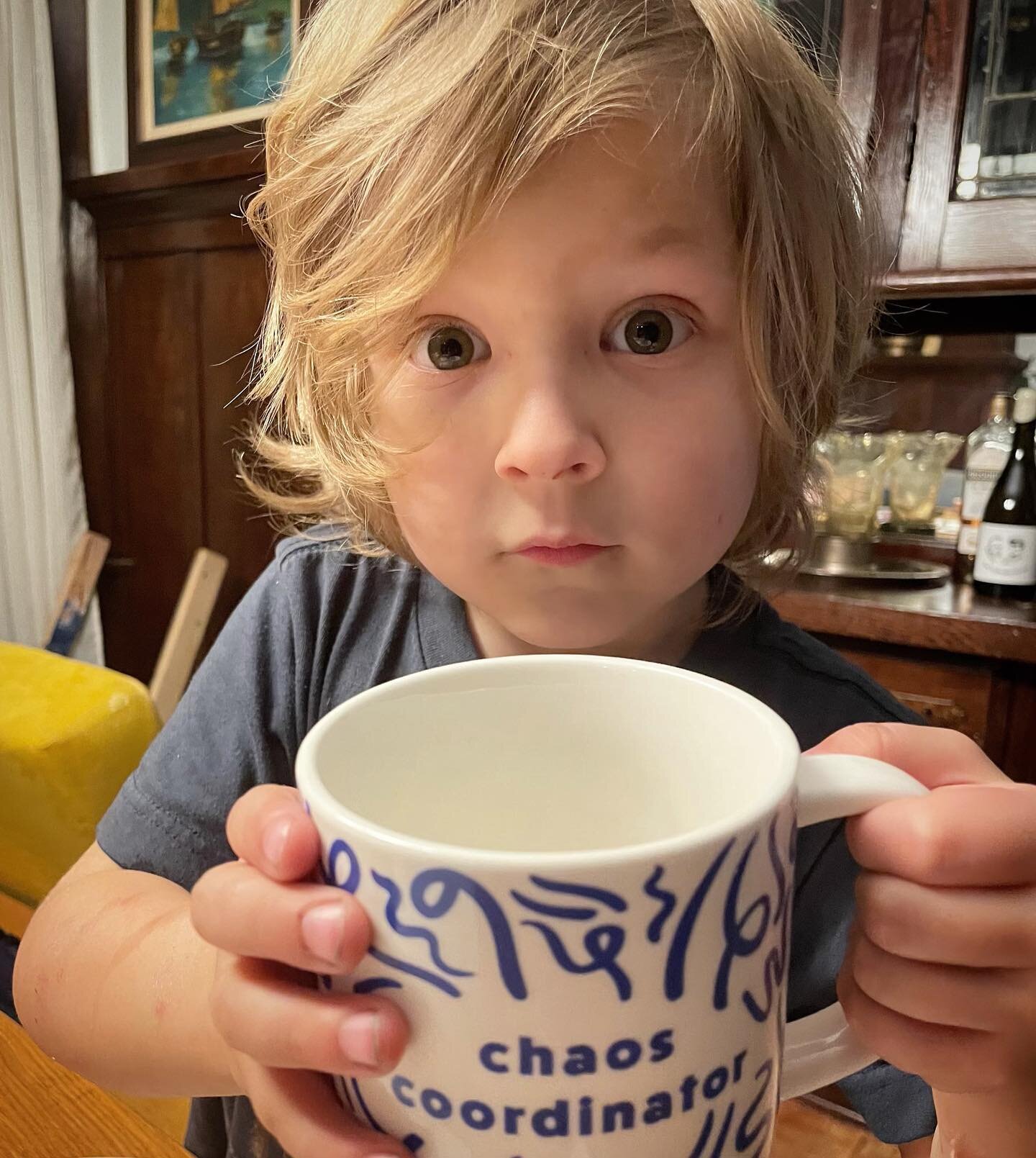

The only photo I have of my mom with Henry.

She told me she was afraid of me. She told me we are just very different people, who have made very different choices. I’m not sure what any of that means.

She told me she wasn’t sure she could be better, that she didn’t think she could change. I believe her.

I told her she knew where to find me, if she ever changed her mind. And that I love her.

The thrust of it is, as far as I can tell, the more emotionally healthy I became, the less she wanted to do with me. I suppose I should take her nearly complete exit from my life as a compliment, but that’s not what it feels like. In spite of all of this, or maybe, because of it, because my own dysfunction runs so deep, I miss her.

I probably always will. Mothering without a mother is very strange thing. I always knew that she wouldn’t be the type of grandma who would watch my kids or fold my laundry, but I never anticipated this complete detachment. I reach for the phone and stop myself several times a week, save myself the pain of her not picking up or, often worse, the panic in her voice, the mad scramble of excuses as to why she has been absent from our lives this week, this month, this year, last year, and on and on. By not calling, I spare us both.

I wish I was better at pretending that it didn’t hurt as much as it does. I don’t regret the hurt though. It’s a sharp reminder of the kind of mother I want to be, especially as my kids enter adulthood: available, accepting, loving, supportive, and able to set my own shit aside when it stands in the way of my relationships with people I care about.

I’m sure there is another side to this story, a side where I have wounded her in ways I don’t know or understand. I’m sure this estrangement hurts her too, even as I know the thought of the work of mending it, is more painful for her than the strategy of numb avoidance she is currently employing.

Today, however, I am left with a family of my own making that I love, friends of my own choosing whom I adore, and a wider community of people that I value and feel valued by. As of right now, my mother isn’t included in any of those groups by her own choosing.

When people tell you who they are, and what they are capable of, believe them.